Julius Caesar

The Rise and Fall of Rome's Most Famous General

The Early Life of Julius Caesar: From Noble Roots to Rising Power

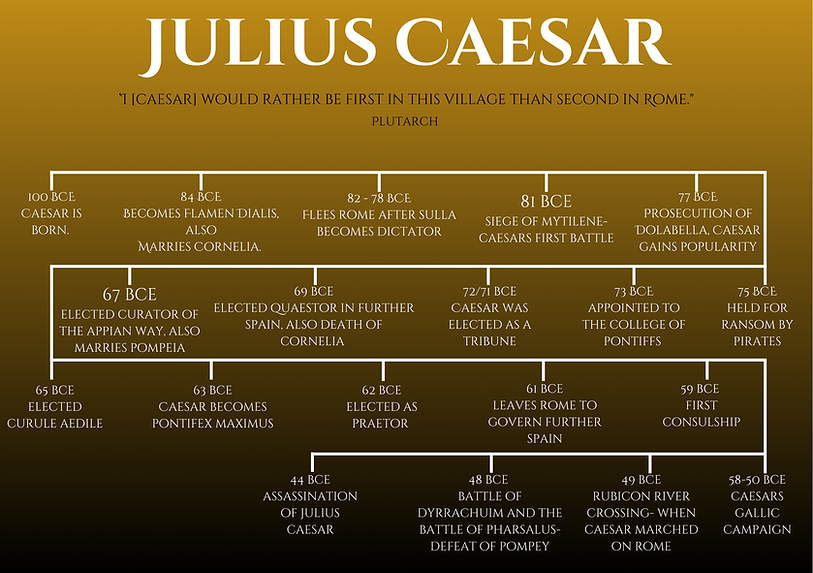

Gaius Julius Caesar was born on July 13, 100 BCE. His family, the Julii clan, claimed descent from the Roman goddess Venus but had lost much of their political influence by the time of Caesar’s rise. His father, a minor senator, died unexpectedly when Caesar was 16—reportedly collapsing while putting on his shoes. Caesar’s aunt, Julia, was married to the powerful Gaius Marius, who was elected consul seven times—five consecutively—and achieved military victories over King Jugurtha of Numidia in 105 BCE and the Gallic tribes, the Cimbri and Teutones, in 101 BCE. Caesar’s mother, Aurelia, came from a prominent family; her father, Lucius Aurelius Cotta, had been consul in 119 BCE. She had three children with Caesar’s father, including two daughters, Julia Major and Julia Minor. After her husband’s death, Aurelia remained a widow until her own death when Caesar was 46. Following his father’s death, Caesar broke off an engagement to Cossutia, whose family lacked senatorial status, and instead married Cornelia, daughter of Lucius

"Experience is the teacher of all things."

Cornelius Cinna, consul from 87 to 84 BCE. Before Marius’s death, he and Cinna secured Caesar the position of Flamen Dialis—despite his young age—giving him early entry into the Senate and a vital start to his political career.

Julius Caesar and Sulla: How Caesar Survived the Dictator's Reign

Caesar lost his position as Flamen Dialis when Lucius Cornelius Sulla became dictator in 82 BCE. Caesar’s uncle Marius and his father-in-law Cinna had waged a civil war against Sulla—Marius died early from natural causes, while Cinna continued the conflict until his own men killed him in 84 BCE. Marius’ son died—either in battle or by suicide—during the siege of Praeneste in 82 BCE. After gaining control, Sulla issued proscriptions targeting his enemies, leading to the execution of many influential figures. Although Caesar, just 18 at the time, hadn’t participated in the conflict, he soon attracted Sulla’s attention. Ordered to divorce Cornelia, Cinna’s daughter, Caesar refused and had his dowry seized. He fled Rome but was captured by Sulla’s men, only securing his release by bribing them with 12,000 denarii. Ultimately, his mother Aurelia and her powerful connections, including Caius Aurelius Cotta, persuaded Sulla to pardon him. Sulla reportedly remarked, “In this Caesar, there are many Mariuses.”

Queen of Bithynia

Though pardoned, Caesar chose to leave Rome and didn’t return until after Sulla’s death in 78 BCE. From 81 to 78 BCE, he served under Marcus Thermus, governor of Asia Minor. Caesar’s family name was still respected in the region due to his father’s previous governorship in 91 BCE. During this time, Caesar was tasked with securing warships for a campaign against Mytilene. He traveled to the client kingdom of Bithynia and successfully persuaded King Nicomedes to provide the ships. However, rumors emerged that Caesar became Nicomedes’ lover—a claim that followed him for life, earning him mockery from political rivals with names like “Queen of Bithynia.” Caesar reportedly lost his temper over the rumor in later years. Despite the scandal, he distinguished himself in the campaign and was awarded the Corona Civica, the highest honor for a Roman soldier. He was later transferred to serve under Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus, governor of Cilicia.

When Caesar Was Kidnapped by Pirates

In 75 BCE, Caesar set out for Rhodes to study rhetoric under the renowned Apollonius Molo, whose former students included Cicero. En route, his ship was captured by pirates. Caesar famously mocked his captors, insisted they raise his ransom from 20 to 50 talents—claiming he was worth more—and regularly entertained them with speeches, joking they were too illiterate to appreciate them. He also warned them he would have them crucified once freed. After the ransom was paid, Caesar raised a small force, tracked down the pirates, reclaimed the ransom, and captured them. True to his word, he had them crucified—though he slit their throats first as an act of mercy to spare them prolonged suffering. He then continued to Rhodes to study, but by 74 BCE, he left to repel raids by Mithridates in Asia Minor. Returning to the region where he had previously raised troops, Caesar quickly defeated the raiders.

The Gallic Wars: Julius Caesar's Rise to Power

58-50 BCE

In 58 BC, Julius Caesar began his legendary Gallic Wars — a military campaign that transformed both Rome and Europe. Over nearly a decade of conquest, Caesar led his Roman legions across Gaul (modern-day France, Belgium, and parts of Germany), defeating powerful tribal confederations like the Helvetii, Belgae, and Arverni under Vercingetorix. His victories not only expanded Roman territory to the Atlantic but also showcased his genius for strategy, engineering, and propaganda. The Gallic Campaign turned Caesar from ambitious politician to unstoppable commander — and set the stage

for the fall of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Caesar's March Across the Rubicon: How the Civil War Against Pompey Began and Finished

When Julius Caesar crossed the River Rubicon in 49 BC, he set Rome on a collision course with its own destiny. Once allies in the First Triumvirate, Caesar and Pompey the Great became bitter rivals in a struggle for absolute power. Their conflict would tear the Roman Republic apart, leading to one of history’s most dramatic civil wars. What drove these two giants of Rome from friendship to open war — and who would emerge victorious?

The Assassination of Julius Caesar: The Ides of March, 44 BCE

On March 15, 44 BCE, Gaius Julius Caesar was stabbed 23 times inside the Theatre of Pompey. His assassins included not only political rivals but trusted allies from his campaigns in Gaul and the civil war—men like Decimus Brutus, Gaius Trebonius, and Servius Galba. The conspiracy was led by Marcus Brutus and Cassius Longinus, both of whom Caesar had previously pardoned for siding with Pompey.

Though Caesar had received warnings—including a letter from a Greek man named Artemidorus and pleas from his wife Calpurnia, who had dreamt of his death—he ignored them. Decimus Brutus, tasked with ensuring Caesar's attendance at the Senate, persuaded him to go despite Calpurnia’s protests. Upon arrival, Mark Antony, Caesar’s ally and general, was deliberately kept away by Trebonius.

At a signal from Lucius Tillius Cimber, the conspirators attacked. Caesar, realizing his fate, drew his toga over his head and collapsed under a hail of stabs. Though the assassins believed they were saving the Republic from tyranny, chaos erupted in Rome, forcing them to flee. In the aftermath, Caesar’s will granted every Roman citizen 300 sestertii, and his great-nephew Gaius Octavius—now his adopted son—received the bulk of his estate.